Inequities in Emergency Preparedness

Before her internship wrapped up, we asked our intern Burgin Utaski to reflect on the heatwaves and emergency preparedness in Portland.

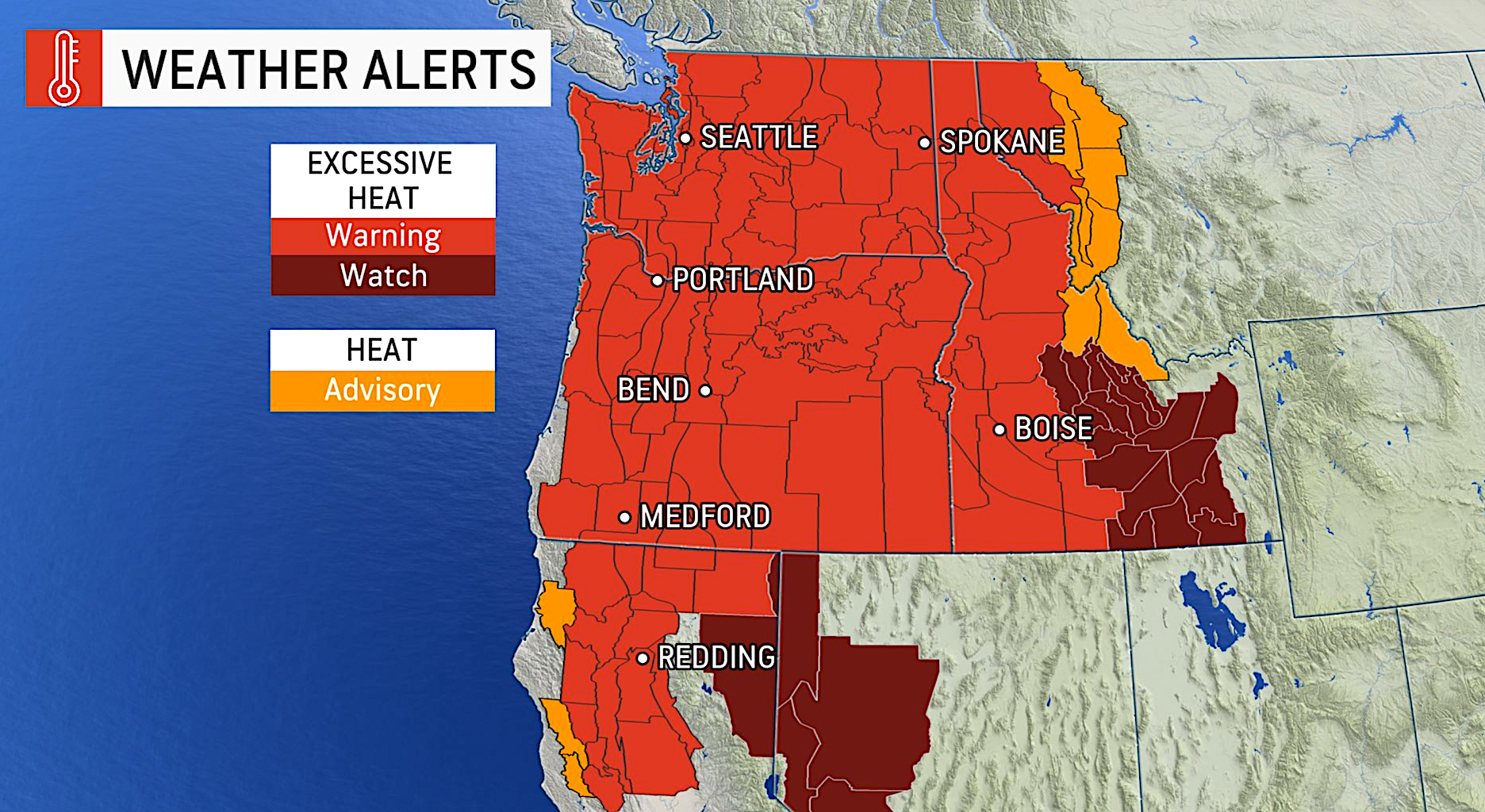

With the chilly and wet weather here, the summer heat waves may seem like a distant memory to many. It is hard to forget that here in Portland, we experienced a record high of 116°. Stepping outside during those few 110°+ days in late June, I found myself unprepared for the overwhelming and all-encompassing heat reflecting off the concrete of the downtown Portland areas. As we now enter the cooler months of the winter, it is important to reflect on our experience in that initial Portland heatwave. As uncomfortable as the heat was for each one of us, we can all recognize that it did not have the same effect on Portlanders equally. An estimated sixty Portland residents died due to the heat, many of whom lived in apartments or multi-family units without air conditioning. A higher number of deaths was seen from lower-income areas, specifically areas with fewer trees and increased proximity to heat-absorbing surfaces like highways and parking lots.

It has become well-known that marginalized communities are at an increased risk of death due to climate-related disasters. This is no less true with climate-related heatwaves. Following the June heat, I wanted to learn more about the inequities in disaster preparedness, especially as I moved forward with Lloyd EcoDistrict’s development in Lloyd emergency preparedness projects. What I came to find is that there are many resources for emergency preparedness, including the Portland Bureau of Emergency Management (and the corresponding Neighborhood Emergency Teams (NET) and Basic Earthquake Emergency Communication Node (BEECN)), Regional Disaster Preparedness Organization, Oregon Office of Emergency Management, and the American Red Cross Cascades Region.

With a plethora of government-funded resources, the question is: How did so many Portland residents still lose their lives in this heatwave? What preparedness measures weren’t taken by those tasked with promoting emergency readiness in Portland? While groups like NET and community organizations, and public agencies, did most likely save lives during that week — members were calling non-air-conditioned apartments and their residents to do safety checks — the truth is that the inequities in these deaths run much deeper.

In early July, I was introduced to the documentary Cooked: Survival by Zip Code, directed by Judith Helfand. Of the many points made in this well-made documentary, one especially stuck with me – we need to rethink how we define disaster preparedness. The film’s story was centered around the tragic 1995 Chicago heat wave, wherein one week, 739 citizens died. Of these Chicago residents, the majority were poor, elderly, Black, and living within the same neighborhood. In the words of Helfand, the event was a “natural disaster that revealed an unnatural one.” This unnatural disaster, the effects of many years of systemic racism, wealth inequality, and redlining, can be seen across all major cities in the US. Helfand notably outlines that while disaster response is extremely well funded, preventative resources put into at-risk communities are not. She attributes this overfunding to the belief people in disaster or emergency are paid attention to because there is an understanding that the situation isn’t their fault.

With this definition of preparedness, it is easy to make parallels to systemic racism and wealth inequality in the United States. These disadvantages are built into the very structure of our country, and are therefore not the faults of any individual. So why aren’t these inequities handled in the same way? Helfand pointedly asks the question: “isn’t there a way to just think about economic development as disaster preparedness?” Want to watch the documentary? Click here.

As we move forward, more extreme weather will inevitably hit Portland, making it essential to recognize these disparities in disaster preparedness and find ways to take action yourself. I urge Portland leaders and the Lloyd community to look deeper into the underlying causes of deaths caused by extreme weather. Which community members are at greater risk? How can funding be redistributed to prepare at-risk residents before an emergency event? This, of course, is not a simple solution and requires an in-depth look at the government funding and structure of Portland as rent prices increase, houseless populations rise, and more Portlanders become at-risk.

Individually, one simple way to prepare you and your community for emergencies is to sign up for the Portland – Vancouver area’s Public Alerts system. Simply knowing about the presence of emergencies in your area can promote better community safety.